|

|

|

|

|

Brigham Young High School History

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The origins of famous "Y" on the mountain above Provo, Utah, are found in friendly, rowdy rivalries between classes at Brigham Young University High School (1876~1968).

During the 1905-1906 school year, high school juniors -- the Class of 1907 -- devised a plan to assert their superiority over the other classes. They selected March of 1906 for their project, after the snow had disappeared from the steep mountain just east of the new Upper Campus.

Before dawn one Saturday morning, they shouldered sacks of white lime and began to hike their way up the side of the mountain. About halfway up the mountainside, in bold view of everyone in the valley, they began to create their graduating year "1907" in a relatively bare patch.

The BYH seniors and other classes were outraged, and they declared war on the upstart juniors. A massive invasion of the mountainside began.

The '07s held out as long as they could, but they were finally driven from their positions, and their lime-white monument was quickly obliterated. Individual '07 class members were hunted down, and their heads were shaved.

|

|

|

It was not the first time that graduation year numerals had appeared, sometimes on the side of an empty building, a watertower, or a nearby mountain. But it WAS the first time a junior class had attempted to eclipse a senior class in the rustic old tradition, triggering violent reprisals.

This new threat to the peace of the school and community constituted a serious challenge to school administrators.

BYH Principal Edwin S. Hinckley immediately called a meeting with elected student leaders and BYU President George H. Brimhall. President Brimhall understood the competitive nature of high school classes because he had served as principal of BYH several years earlier, from 1895 to 1900.

They all knew that such rivalries could be healthy, serving to create a valuable bond between students, cementing life-long friendships and giving strength to future alumni loyalty. At the same time, however, emotions had to be kept in check to avoid vandalism and violence.

Each class was already encouraged to create a banner, a slogan, and sometimes a cheer, although the competing cheers grated on the nerves of some of the older members of the Board of Trustees.

This particular brawl on the mountainside called for an exceptionally creative and rapid administrative solution.

One idea came from the faculty. The Board and administrators had a long tradition of encouraging faculty members to further their education during the summer months at various universities around the nation. A few faculty members each year chose to take summer classes at the University of California at Berkeley.

One year earlier, in the spring of 1905, freshman and sophomore classes at UC-Berkeley had cooperated to create a 70-foot "C" in the Berkeley Hills, just in time for the school's annual Charter Day celebration.

BYH and BYU faculty members who took classes there during the summer of 1905 saw the giant "C" and returned home talking about the possibility of placing large B-Y-U letters on the mountainside above Provo.

As the Class of 1907 incident developed, high school and university leaders seriously began to consider the idea of painting the school initials on the mountainside in a dignified, monumental manner. They hoped this would unite the classes, and forestall graffiti vandalism by future classes.

Preparations for placing the university's initials on the mountainside began in April of 1906 when President Brimhall commissioned surveys for the letters B, Y, and U. The letter "Y" was laid out first to insure that the initials would be properly centered on the mountain.

Professor Ernest D. Partridge was asked to design the emblem and supervise its survey in 1906. He had taught Brigham Young high school and collegiate students in mathematics, agriculture and theology since 1897, and was an expert surveyor.

|

|

|

Three of Professor Partridge's students, Elmer Jacob, Clarence Jacob, and Harvey Fletcher, climbed the mountain and staked out the outline of each letter.

According to Dr. Harvey Fletcher, BYH '04, BYU '07, who later became one of the nation's most honored scientists, the survey was made by sighting the mountain locus from the top of the "High School Building" as the historic Education Building was then called.

When the outlines were complete, the center letter "Y" measured 322 feet in height and 120 feet in width. The school purchased 380 acres on the face of the big mountain east of of the Upper Campus, extending clear to the top of the mountain, for the project.

From the air, the letters would appear elongated, but they were intentionally designed that way so that they would look normal from the valley floor.

|

|

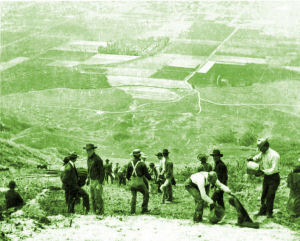

Students spread lime on the first Y - 1906 |

|

Hot lime was carried up in 1908 |

|

Dr. Fletcher, in his autobiography, recounts how the high school and college students participated in that first Y Day:The students stood in a zig zag line about 8 feet apart stretching from the bottom of the hill to the site of the Y. The first man took the bag of lime, sand or rocks and carried it 8 feet and handed it to the next man. The second carried it another 8 feet and handed it to the third man and thus the bag went up the hill, each man shuttling back and forth along his 8-foot portion of the trail.

All the students started with enthusiasm as they expected to be through by 10 o'clock a.m. But it was a much bigger job than anyone expected. It was 4 p.m. before the Y was covered, and then only by a thin layer. So no attempt was made to cover the other two letters.

It was very hard work and most of the boys had had no breakfast and no dinner. No one dared to quit as it would break up the line. In the afternoon it was more than some of them could take and they fainted and had to be helped down the hill.

I am sure those who worked in that line that day will never forget it. They were somewhat rewarded when they got back to campus and looked at the beautiful white Y on the mountainside in just the right proportions. It looked like it was standing in the air just above the ground. The original Y consisted of only a thin layer of lime powder, and was in constant need of repair. Students showed their loyalty to their class and to the school by climbing the mountain each year to give the Y a fresh coat of lime.

Hoping to make it more permanent, a layer of rock was added in 1907. The next year, 20,000 pounds of sand and cement were carried up the mountain to form a three-foot high wall around the letter to hold it together.

At first, it was a plain letter, but in 1911 it was made into a block "Y" with the addition of serifs at the tops and bottom, forming its current appearance.

Every spring, students organized themselves into groups and assisted in cleaning up the campus and community of Provo. The event was called "Y Day", and most of the morning was spent in whitewashing the "Y".

|

|

|

Students formed a human chain from the base of Y Mountain to the "Y". Every year it was built up a little more with stones and cement, then whitewashed by thousands of students hauling thousands of gallons of lime mixture up the mountain using a bucket brigade. They passed a mixture of water, lime, and salt from hand to hand until it reached those assigned to spread the whitewash. This tradition lasted for over six and a half decades.

Beginning in 1975, the letter was whitewashed with the aid of a helicopter to reduce erosion problems on the mountainside.

Five times a year Y Mountain flares to life -- for Freshman Orientation, Homecoming, Y Days, and April and August graduations.

The Intercollegiate Knights, a club dedicated to chivalrous principles and maintaining school traditions, performed the ritual.

In earlier years the members of the Intercollegiate Knights carried torches up the mountainside to light buckets of kerosene-soaked mattress batting placed around the edge of the Y.

In later years, the Knights rolled out a cord of lights around the border of the Y. Streams of students climb up to the Y during those days.

|

|

Lighting the Y with fire in 1924. |

|

Lighting the Y with electricity today. |

|

After several decades, when it was decided that the kerosene was too dangerous, a generator was placed nearby to power 25-watt light bulbs through the night.

Members of the club remained on the mountain through the night to watch over the lights and insure that they remained lit through morning.

On such nights, the dazzling symbol of BYU can be seen from the far reaches of the valley.

|

|

|

Now a nationally recognized symbol of BYU, Y Mountain is a featured shot of almost every BYU game broadcast on television. Located about one-half mile east of campus and halfway up the mountain, the Y looks out over the valley and is one of its most prominent features. Hiking up to the "Y" takes an hour or two, depending on the condition of the hiker, and the view of the campus and Utah Valley is spectacular.

Would it have happened without the upstart juniors in the BYH Class of 1907, and the crisis they caused?

|

|

Y Mountain from the Abraham O. Smoot Building |

|

Provo's famous alpenglow on Y Mountain |

|

In September 1978, a BYU alumnus wrote a letter to the Editor of the BYU Daily Universe proposing that the two missing letters be added to Y Mountain (B and U, of course), as had been originally intended.

The subsequent letters section held a tongue-in-cheek response from Norman A. Darais, BYH Class of 1964:

Editor:

Let's carry this good suggestion a little further. Why not add ALL the letters in the school name -- since we would only need 21 more. Or maybe we should consider covering the entire mountain with concrete. Then we could paint whatever we want on the mountain, or, for the ultimate touch of class, we could cut the school letters out through the concrete facade. In so doing, the letters themselves would be displayed through the concrete in beautiful mountain colors (which would change with the seasons). Covering the entire mountain with concrete, although somewhat expensive initially, would also eliminate any future worries of erosion.

Or maybe not.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BYU climbs a mountain — to buy Y Mountain

|

|

By Annie Knox | The Salt Lake Tribune

March 31, 2016

Brigham Young University has become the sole owner of its signature landmark — and all it took was $180,000, four years and an act of Congress.

With Y Mountain now the exclusive property of the private Provo school, students, alumni and outdoors enthusiasts are celebrating. They expect the land-ownership transfer from the U.S. Forest Service to improve safety on the steep one-mile path that leads to the block letter.

The thought of upgrades is reassuring for 2001 BYU graduate Leslie Findlay, who ran the trail as a student and hiked it when she was pregnant with her first child, Hugh, now 12. When the boy was 3 months old, Findlay hiked to the Y at night with Hugh and husband Jacob to illuminate it with lightbulbs, part of an annual homecoming tradition.

Even after moving back home to Arizona, returning to the path remains a ritual on yearly visits back to Utah.

"Once you get to the Y, it's really steep and it's kind of scary now," said the piano teacher and mother of six. "Having kids, it makes me nervous to take the babies all the way up."

The Findlays' university now can alter the path without consulting with the Forest Service. The school, owned by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is already planning a series of upgrades to repair erosion on switchbacks and the summit, which requires some scrambling.

The additional 80 acres surrounding the top two-thirds of the letter cost $180,000, according to Utah County records of the transfer dated February 16th.

U.S. Rep. Jason Chaffetz, who was a BYU football kicker, brought a 2012 resolution allowing the transfer at his school's request. The Utah Republican told lawmakers at the time that BYU wanted to provide water on the route and had the resources to better clean up litter.

But it was another Utah Republican and BYU alumnus, Sen. Orrin Hatch, who successfully tucked permission for the transfer inside a national defense bill last year. Provo Mayor John Curtis also lent a hand, testifying in favor of the legislation.

The law is personal for Hatch, who graduated with a history degree in 1959.

"I have fond memories of hiking up the mountain as a BYU student with buckets of water, lime and salt to whitewash the Y," the senior senator said through a spokesman. "Y Mountain has always been a special place to me, and I am glad that future generations of students will be able to enjoy it as well."

BYU President Kevin Worthen celebrated his school's new deed for 81 acres of forest land, noting the icon painted to the east of campus is one of the first things campus visitors spot.

"We intend to make sure," Worthen said in a statement, "the Y continues to stand as a welcoming symbol to all who come to Utah Valley."

The history of the letter, 380 feet tall and 130 feet wide, dates back more than a century, when members of the junior class at the former Brigham Young High School lugged sacks of lime up the mountain to paint their graduation year on the dirt. Other classes retaliated by erasing the "1907," according to the high school alumni group's Web page.

Administrators put an end to the scuffle by commissioning a mathematics professor and his students to write "BYU" on the mountainside above the upper campus.

But Harvey Fletcher later wrote in his autobiography that the daylong project proved too much for the workers. After completing the Y, the crew abandoned plans for the other two letters. Some fainted on the way down, Fletcher wrote. They hadn't thought to pack breakfast or lunch.

Students such as Hatch followed the same path each spring to whitewash the Y until the mid-1970s, when a helicopter was brought in to do the chore. It now is covered in concrete and illuminated five times per year: freshman orientation, homecoming, Y Days and graduations in April and August.

Repairing the erosion will take some time, the school acknowledged, adding that hikers and runners should expect intermittent closures this year. And while BYU hopes to improve access for many, not every type of adventure will be welcome.

As a freshman in fall 1969, Mark Emmet attempted to drive his 1957 Chrysler more than halfway to the north end of the trail before he got stuck.

"I can't remember," he wrote via The Salt Lake Tribune's Public Insight Network, "how we managed to get the car turned around and off the mountain."

Source

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|