|

|

|

|

|

|

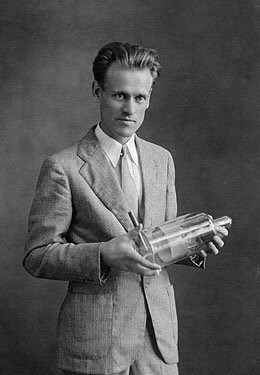

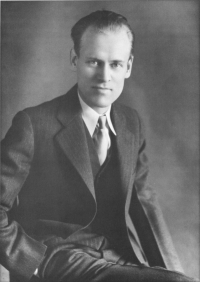

Mathematician, Inventor,

Father of Electronic Television

|

|

|

Philo T. Farnsworth,

Father of Television

1906 - 1971 |

|

|

Brigham Young High School

Class of 1924

|

|

|

Editor's Note: We are grateful to Kent M. Farnsworth, son of Philo T. Farnsworth, for reading and correcting biographical details that were previously hazy or incorrect. These changes were made on October 28, 2006. Kent, thank you for your kind help! For those who wish to learn more of the correct story, Kent recommends one of his mother's books, Distant Vision by Elma "Pem" Farnsworth. Copies can be purchased from KBYU, Amazon, eBay, or you can visit the Farnsworth family website.

|

|

|

Who is the most influential graduate in the history of Brigham Young High School?

The answer to this question, given without any hesitation, is Philo T. Farnsworth, BYH Class of 1924, the man who invented electronic television.

A friend of his once commented that Philo, at the age of 14, dreamed of trapping light in an empty jar, from which it could be transmitted. Philo was never that naive or simplistic.

It is more accurate to say that at the age of 14, he dreamed of using a lens to direct light into a glass camera tube, where it could be analyzed in a magnetically deflected beam of electrons, dissected and transmitted one line at a time in a continuous stream. And he would have had an even more accurate description.

In 1927, at the age of 21, he produced the first electronic television transmission. He took a glass slide, smoked it with carbon and scratched a single line on it. This was placed in a carbon arc projector and shone onto the photocathode of the first camera tube.

The first camera tube used a phosphor on the photocathode that was not sensitive to light, as were the phosphors that they developed later. Phosphors, at first, were not really sensitive to light, so the lights used to illuminate objects to be televised were extremely bright and very hot; too much for human subjects to endure.

Many improvements were made in the next few years, and by 1930, Phil's wife Pem was able to sit for the camera for a few moments before she had to turn away. By 1930, Farnsworth produced an all-electronic television image using his wife, Pem, as the first human subject to be transmitted on television. She was again televised in 1931, and she still had to partially turn away from the camera because the lights were so hot, and move away completely after a few moments.

In the fifties, camera tubes were developed that were much more sensitive. Lights could be cooler, and actors were more comfortable. In the sixties the hot lights returned with the advent of color, at least until television engineers developed better color cameras.

Farnsworth filed Patent #1,773,980 for his camera tube, entitled Television System, on January 7, 1927 and was granted the patent on August 25, 1930, after a long battle with corporate giants.

A second patent was needed to begin the whole television story; Patent #1,773,981 which he obtained for the cathode ray tube (CRT) providing the display tube -- the receiver -- the television screen.

According to his wife, Pem Farnsworth, "Phil saw television as a marvelous teaching tool. There would be no excuse of illiteracy. Parents could learn along with their children. News and sporting events could be seen as they were happening."

She added, "Symphonies would mean more when one could see the musicians as they played, and movies would be seen in our own living rooms. He said there would be a time when we would be able to see and learn about people in other lands. If we understood them better, differences could be settled around conference tables, without going to war."

Later in his life, his attitude was tempered by the reality of commercial television programming. His son Kent was once asked about his father's attitude. Kent reported, "I suppose you could say that he felt he had created kind of a monster, a way for people to waste a lot of their lives. Throughout my childhood his reaction to television was, 'There's nothing on it worthwhile, and we're not going to watch it in this household, and I don't want it in your intellectual diet.' "

According to Kent, his father would have reacted very well to cable programming like The Cooking Channel, Discovery, National Geographic, The Learning Channel, and similar fare. "For learning via television to be accessible and worthwhile, he understood it should be fun too. These mini-networks would have pleased, even surprised him."

Philo Taylor Farnsworth was born on August 19, 1906 to Lewis Edwin and Serena Bastian Farnsworth, in a log cabin at Indian Creek near the tiny town of Beaver in southern Utah.

How did the Farnsworth family happen to be living in this remote farming community? In 1856, Brigham Young had issued a call to his grandfather to move from Salt Lake City to settle this community.

By the age of six, Philo had encountered the hand-cranked Bell telephone, which astonished him. He spoke to his Aunt who was far away, yet her voice was as clear as if she was standing beside him.

His father, recognizing his son's enthusiasm, explained to Philo that inventions like Bell's telephone and Edison's light bulbs and gramophone were created by people who had dedicated their lives to creating innovations. These people, his father explained, were called "inventors".

Philo decided that he wanted to become an inventor. He began to observe problems around him that could be solved by new inventions. During his lifetime, he had applied for and received more than 130 patents on his inventions.

When he was 12, the Farnsworth family moved to his Uncle Albert's 240-acre ranch near Rigby, Idaho, to sharecrop. The ranch was four miles from the nearest high school, so Philo rode to school on a horse each day.

As a thirteen-year-old boy in 1919, Philo was delighted to find that his uncle's farm had electricity. He read everything about electricity that he could find, including the technical instruction manual to the Delco power system that provided power for the farm.

Soon Philo had figured out how to use electricity to operate the family's washing machine, sewing machine, and barn lights. Still just thirteen, Farnsworth won a first prize of $25 for his invention of a theft-proof ignition switch for automobiles.

Philo discovered a cache of science magazines like Popular Science in the attic of the old farmhouse where the Farnsworth family took up residence.

It was in these magazines that Philo read about a then favorite topic of science writers such as Hugo Gernsback: television.

Sending pictures through the air was no more fantastic than broadcasting speech and music using radio waves, but no one had figured out how to send or receive images.

Radio itself, in 1922, was in its infancy. There were only 30 licensed broadcasting stations in the United States. There were no stations yet in Idaho, and only one in Utah. But due to lack of interference, radio transmissions could be received from great distances.

Sending pictures through the air started out as a fascinating diversion for this young boy, and grew into an intense preoccupation as he grew older.

But plowing or disc-harrowing potato and hay fields all day gives one an abundance of time to think. After a while, a good plow horse knows when it is time to turn the plow and start the next row: a time for boredom or inspiration.

|

|

|

When Philo looked over the newly plowed field as he was finishing, he saw evenly parallel lines, row after row. It occurred to him that an image could be sliced into such rows, back and forth, and then each row transmitted in a continuous sequence. Thus the "raster" image was born.

It was at Rigby High School that Philo met Mr. Justin Tolman, who was his chemistry teacher. Philo persuaded Mr. Tolman to give him special instruction and allow him to audit a senior course.

Throughout his life, Farnsworth gave credit to Tolman for providing inspiration and vital knowledge to him at this critical time in his life.

Years later, Mr. Tolman was able to testify at a patent interference case, producing a small paper diagram that he had saved years earlier, decisively proving that Farnsworth was the original inventor of television.

During that testimony, Tolman provided vital insights into Farnsworth's intelligence as a young student. Tolman said Farnsworth's explanation of Einstein's theory of relativity was the clearest and most concise he had ever heard. And that was in 1921 when Farnsworth was still 15!

|

|

|

|

It was Tolman's detailed recollection of the conversation -- and the small diagram on paper that he had saved -- that later played a part in the patent interference hearings between the Farnsworth Corporation and RCA.

During one year at Rigby High School, Farnsworth completed two years of algebra and a year of chemistry, as well as completing National Radio Institute correspondence courses.

The next year, while working as an electrician's assistant in Idaho, he took an additional four correspondence courses from the University of Utah.

At the end of the school year, Philo borrowed a few more books from Tolman. As the two parted, Farnsworth asked Tolman if he could give him some advice that might help him realize his ambition of inventing television. "Study like hell and keep mum," Tolman is said to have replied, although that may be myth.

|

|

|

Rigby High was a memorable experience not only for Philo but also for Tolman, who later captivated generations of students with his stories about young Farnsworth.

He told them about how young Philo had drawn diagrams of his image dissector, and how Tolman had saved one of them. He showed the tiny diagram to each new class at the beginning of a school year, and talked about his own 1934 testimony before the patent hearings.

In 1923, the Farnsworth family moved from Rigby to Provo, Utah, hoping to increase the educational opportunities they felt a university town had to offer their children.

They rented one side of a duplex home near Brigham Young University. A Gardner family rented the other side. Income for the Farnsworth family came from what Philo's father made from working the Idaho farm, and in road construction, and what his sons could make doing odd jobs.

|

|

|

Farnsworth attended Brigham Young High School on the Lower Campus beginning in fall of 1923 until he graduated in the following June in the Class of 1924.

Tragedy struck in January 1924. Philo's father caught a cold while returning home to Provo from a construction job in Idaho. The cold turned to pneumonia and he died at the age of 58.

His father's death was catastrophic for Philo. As the oldest son, he assumed the obligation for sustaining his family, yet he still had six months of high school left before graduation. He concentrated and graduated with his class.

According to his sister Laura, Philo felt responsible for his brothers and sisters. "He had such a paternal feeling about us that sometimes it felt like he wasn't letting us make up our own minds."

Farnsworth's anguish was understandable. He and his family had left a supportive family, teacher and school in Rigby. When his father died, it evoked many emotions and unanswered questions -- Why would God take his father just when he was needed most?

Philo could not understand, and he did not return to the church of his heritage until the final years of his life. The death of his father challenged his faith, yet at the same time strengthened his independent spirit.

Like the line upon line he had plowed into the fields of the farm in Idaho, lines that inspired the concept of raster lines vital to television, late in his life he finally reassembled and recognized the full picture of his life. Each line and each tragedy had played a part in helping him fulfill his inventive creativity.

Farnsworth enrolled at Brigham Young University in 1924. He was still in a hurry and quickly acquired the run of the BYU research laboratory. However, BYU science professors were unimpressed with the youthful farm boy and, when he asked to attend advanced classes, was told an exception could not be made.

Being told "No" created a new motivation for Philo. He redoubled his efforts to study science on his own and earned his Junior Radio-Trician in 1924 and his Certified Radio-Trician in 1925 from the National Radio Institute.

Farnsworth was not only an inquisitive student but also an accomplished musician. He was a member of the high school dance orchestra and later the Brigham Young University chamber music orchestra. He played both the piano and the violin. He loved music, and later in life, music was one of the few ways he could relax. He also took part in school plays.

It was during his days at BYU that Philo met the woman who would play a central part in his life -- Elma "Pem" Gardner -- then attending Provo High School.

|

|

|

|

Pem G. Farnsworth, 1st electronic TV star! |

|

The courtship of Philo Farnsworth and Pem Gardner included such activities as ice cream socials, dances and going to "radio parties" at BYU. Pem had taken serious piano lessons for many years, and Phil was accomplished on violin. Pem's brother, Cliff, played the trombone. When they realized that they had a love of music in common, they would often find an empty hall with a piano and rehearse together. Philo and Pem also liked to dance.

Living in Provo also provided work opportunities. One possibly apocrophal story says that Farnsworth asked and received permission to hang around the local power plant. The plant foreman approved on the condition that he wouldn't meddle with anything.

One day a mysterious trouble halted the plant's operations. Experts were unable to solve the trouble. Philo stepped forward, asked permission to fix the machinery, and set to work. Soon everything was running smoothly, and the plant manager offered him a troubleshooting job on the spot.

After graduating from high school, Philo had no trouble finding work. He worked on logging crews, repaired and delivered radios, sold electrical products door to door, and worked on the railroad as an electrician.

Philo and a friend finally signed up to take the entrance exam needed to attend the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. Philo reasoned that in the military he could provide support for his fatherless family and continue his work in electronics.

Philo ranked second in the nation that year on the results of his Annapolis entrance exam.

It was at the Naval Academy that "Philo" became "Phil" -- the name all of his friends and associates called him. He dropped the "o" from Philo because, he said, he didn't want to be called "Fido". History, however, has restored the "o".

Farnsworth's Navy experience did not last long. A chaplain, hearing more of Farnsworth's story, said to him privately, "You don't want the US Government to own your patents, do you?" Realizing that his dream of supporting his family with income from his inventions was in jeopardy, he took action.

Farnsworth asked his mother to approach a US senator and formally request that her son be given a release from the military. There was a rule stating that the oldest child in a family without a father, could not be drafted into the services because he was needed by his family as the chief breadwinner.

After just a few months of attending classes at Annapolis, Farnsworth moved back to Provo and enrolled at BYU for another year. BYU professors seemed more receptive to him after his short stay in the Navy, and Farnsworth was allowed to take several advanced science classes.

However, finances were still a serious problem, and he worked at a variety of odd jobs to stay in school. During the semester, he worked as a custodian at BYU, and in the summer, he worked with his brother in a lumber mill in Payson Canyon. He worked as long as he could to stay enrolled at BYU, but finally was forced to leave school and seek full-time employment in Salt Lake City.

|

|

|

After moving to Salt Lake City in 1926, he obtained a job installing and repairing radios. There were twelve radio stations in Salt Lake City at the time, but radio repair was not demanding, so Farnsworth registered with the employment office at the University of Utah, and continued his research work at the university library.

One of his jobs involved working on a Salt Lake City street cleaning crew. He became familiar with every street in the city. It was this knowledge that earned him a supervisor position with an out-of-state charitable organization managed by George Everson and Leslie Gorrell.

Everson and Gorrell were professional fund-raisers from California. They were impressed with Farnsworth's street-by-street knowledge of the city, and of his ability to organize a job, dedicate himself to completing each of the tasks involved, and motivate other team members.

As they worked together to perform the mundane work of folding, stuffing, sorting and stamping bulk mailings of fund-raising letters, they began to listen to Farnsworth's ideas about electronic television.

So impressed were these two men of Farnsworth's knowledge of current television literature and his own innovative concepts, they offered to financially support the venture under a formal partnership known as Everson, Farnsworth & Correll.

Three days later, May 27, 1926, Philo and Pem were married. Pem became her husband's assistant during their entire 45-year marriage. She took care of all correspondence and became an expert draftswoman, preparing many of the technical drawings he needed. She provided encouragement and support that allowed Farnsworth to continue his research.

In 1926 Philo and Pem Farnsworth went to California and built a lab in several rooms of a second-story rental space in San Francisco, at the base of Telegraph Hill.

On September 7, 1927, Farnsworth, George Everson and other staff members sat in a room as Farnsworth slowly turned on the controls of his laboratory apparatus. Cliff Gardner, in another room, placed the smoked glass slide inscribed with a single line, into the projector. Cliff directed it towards the camera tube, then rotated it.

Back in the viewing room, an unmistakable line appeared across a small bluish square of light on the end of a vacuum tube. Although fuzzy at first, it became distinct with adjustment. Through the visual static, everyone could see the black line, then watched as it was rotated in the next room. It was a line, not a triangle, as is sometimes reported. This was the first "information" transmitted by electronic television.

"There you are," Farnsworth is reported to have said, "electronic television."

The lab journal entry was more prosaic: "The received line picture was evident this time."

Philo Farnsworth was barely 21 on that historic occasion.

For the next three years, financial support was provided by a group of bankers and investors calling themselves Crocker Research Laboratories.

In March 1929, a man named Jess McCarger was put in charge. The Farnsworth Television company was owned by its stockholders, and Farnsworth was the majority stock holder. The principal capitalization came from a group of bankers, and for this reason, everyone was asked to do as McCarger directed, so he was the general manager. McCarger renamed the company Television, Inc. However, when the company was later moved to Philadelphia, it was again called Farnsworth Television Inc. or FTI.

During the period of 1929 to 1933, publicity catapulted the promise of this little organization. However, with public awareness also came the problems of competition, races to the patent office, and legal disputes. Farnsworth became the subject of industrial espionage, and his central idea was stolen by RCA after an RCA scientist toured Farnsworth's laboratory for three days. Farnsworth was not concerned because his patents were rock solid, but the patent dispute consumed valuable time and energy.

Farnsworth's ace in the hole turned out to be his Rigby High School science teacher, Justin Tolman, who produced the small drawing that Philo had made back in 1922 of his "image dissector" which remarkably resembles the television tube that eventually became the standard "tube" in commercial television. Although it did not constitute legal proof, it gave Farnsworth decisive credibility.

By the age of 64, Farnsworth held more than 300 United States and foreign patents, most of which formed the foundation of the television industry as it swept the world and changed the nature of modern civilization.

At his death, Scientific American called Farnsworth one of the ten greatest mathematicians of his time.

Although best known for his development of television systems, Farnsworth was involved in research in many other areas.

He invented the first electron microscope, and the first infant incubator. He was involved in the development of radar, peacetime uses of atomic energy, and the nuclear fusion process.

Farnsworth built a variation on the tubes he was developing to examine the uniformity of the phosphors he was coating on photocathodes -- it used electrons instead of light. This would later be known as the electron microscope, but he had no time to develop it. Vladimir Zworykin did some additional work on this device.

The first baby incubator was called the "isolette" and was developed at the request of the Farnsworth's family physician in Philadelphia. Farnsworth did not want any credit for that; he was happy to find a means to save premature babies, which this device did on a monumental scale. He made many such contributions to mankind and was happy to help.

Farnsworth's refined picture tube [cathode ray tube, or CRT] was called the "Iatron" and it could store an image for milliseconds to minutes (even hours). One version that kept an image alive about a second before fading, proved to be a useful addition to radar. It is often said that Farnsworth invented radar, which was not true, however, his slow-to-fade display tube was used by air traffic controllers from the very beginning of radar.

Philo Farnsworth spent the first half of the sixties working to develop fusion energy, and sustained a controlled nuclear fusion reaction at ITT/Farnsworth in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Management made several moves to influence the work and change its direction, but Farnsworth wanted nothing to do with research he was not in control of. Farnsworth resigned, and that project made no further progress after he left.

According to his wife, Farnsworth was especially proud when he saw the landings on the moon with the electronic eyes he had invented. The moon landing was a thrill, and Farnsworth was vocal about that, and rightfully so.

Before the moon landing mission, NASA scientists had been unhappy with some late-model commercial modifications to television camera tubes. For this camera to operate in space, it was redesigned using some technology going all the way back to Farnsworth's original image dissector.

In the late sixties, Philo Farnsworth realized that he had uprooted Pem from her family, and that they both had had no time for the church. With his work at ITT/Farnsworth done, he took his wife home to Salt Lake City, bought her a beautiful home, and they returned to the LDS Church to be married in the temple.

Farnsworth died on March 11, 1971. His career as a scientist had been full of ups and downs, and for a time he and his vital contributions were largely forgotten and overlooked by the general public. He said on more than one occasion that he never invented anything; he was only the instrument through which the inventions were made available to mankind.

However, during the next 20 years, the reputation of Philo T. Farnsworth became the subject of increasing research, and his amazing achievements became more widely reported and appreciated.

In 1983, the US Postal Service issued a Philo T. Farnsworth stamp, with a likeness of his face and his first television camera.

|

|

|

In 1988, a museum in Rigby, Idaho was dedicated to Farnsworth, and is called "The Birthplace of Television".

Farnsworth was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame.

On May 2, 1990, a bronze statue of Philo T. Farnsworth, sculpted by James R. Avati, was placed in Statuary Hall in the Capital Building in Washington, D.C., as Utah's second honoree. Each state is allowed two statues. The first honoree was Brigham Young.

|

|

|

This statue honors Philo Taylor Farnsworth as one of the greatest electronic inventors of the twentieth century -- the "Father of Television".

The alumni of Brigham Young High School who followed in Farnsworth's footsteps can compare our own days on the Lower Campus with his BYH school days in 1923 and 1924, because the campus had not changed much between 1903 and 1968, when BYH held its final commencement exercise.

And each time we catch sight of a television screen, we can ask ourselves, how much longer might this invention have taken to appear, and in what lesser form might it have been invented, without Farnsworth's unique insights, including those gained while simply plowing potato fields in Idaho.

|

|

|

|

Philo Taylor Farnsworth was born on August 19, 1906, Indian Creek, Beaver, Utah. His parents were Lewis Edwin Farnsworth and Serena Amanda Bastian. He married Elma "Pem" Gardner on May 27, 1926, and they had four sons: Kenneth Farnsworth (dec.); Philo T. Farnsworth III (dec.); Russell Farnsworth (Rose), in New York City; and Kent Farnsworth (Linda) in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. [@2006] Pem's parents were Bernard Edward Gardner and Alice Maria Mecham. Philo T. Farnsworth died on March 11, 1971 in Salt Lake City [Holladay], Utah at the age of 64. Pem Gardner Farnsworth died on April 27, 2006, in Bountiful, Utah, at the age of 98. Interment, Provo City Cemetery.

~ ~ ~ ~

Justin Tolman was born on April 10, 1889 in Bountiful, Utah. His parents were Judson Adonirum (or Adnyrum) Tolman and Zibiah Jane Stoker. Justin Tolman married Alice Vilate Ashdown on August 27, 1914. He died on May 16, 1957 in Liberty, Missouri at the age of 68.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|